Curator's text

Saša Nabergoj

Tomislav Brajnović (b. 1965) is a Croatian conceptual artist and assistant professor at the Rijeka Academy of Applied Arts. His oeuvre spans more than 30 years and deals with the eternal themes of ideology, religion, the meaning and existence of humanity, art, and the artist’s role in society. He is using different media from spatial installations, videos, graphics, sounds, images, statues, performances, happenings, objects, photographs to Facebook posts.

Sixteen Brajnović’s works from 1988 and 2022 are exhibited in a dialogue with the content of the permanent museum collections (historical, art historical, archaeological and ethnological) and in the chapel and living room of the Škofja Loka Museum.

Tomislav Brajnović was born in Zagreb into an artistic family; his grandfather (the prominent Croatian naive art painter Željko Hegedušić), father (Marčelo Brajnović), mother (Zvjezdana Hegedušić Brajnović) and his two sisters and brother are all artists. After a nomadic life in the 70s and 80s that saw the family move about in Italy and France, they settled at road’s end on top of Golo Brdo hill, a previously uninhabited ancient burial ground (Gomila) above Rovinjsko Selo village in Istria, Crotia, his father’s birthplace. There they have built a cluster of studios and living spaces, followed by a baptistery and a school. Though the ambitious architectural complex, drawn up by his father, remains unfinished, Golo Brdo presents a gesamtkunstwerk, connecting architecture, artistic practices and everyday life of a creative family.

Brajnović was particularly influenced by his father, Marčelo Brajnović, a central figure of Croatian surrealism early in his career. Equally proficient in numerous artistic media, including sculptures, drawings, texts, assemblages, collages, performances, spatial interventions as well as being an outstanding painter of large compositions, Marčelo developed a comprehensive artistic paradigm early in his life, profoundly shaped by the fact that he, unlike most of his artistic contemporaries, believed in the Christian God (though not in the institution of Christianity) and placed God at the centre of its activities. Putting forth the spiritual above the material, ethics before aesthetics Marčelo thus first became an engaged artist/teacher with a plan to build the Sky and Earth Painting Centre where he could teach his students. The project begun with him opening the first building on Golo Brdo in a performance where Marčelo, dressed in a royal coat with a crown and royal insignia, declared himself king. In the early 90s, he renamed the Centre the Embassy of the Kingdom of God on Golo Brdo, assumed the role of a prophet, and developed a unique performance format with dramatic elements that he called performative dramatization as his main artistic tool. He liked to use objects and symbols in his performances as well as devised his own font that he used on posters he put up at public places in the surrounding villages. Using screen printing, these public messages were intended for the broadest public – indeed, for everyone.

Brajnović started exhibiting already in the 80s. In late 90s, he graduated in sculpture at the Zagreb Academy of Arts, and in 2003 he obtained a master's degree from the prestigious St. Martins College in London. He then returned to Istria, becoming a versatile cultural worker and active artist. He established links with local artistic communities and collectives as well as hosted a series of one-day exhibitions by outstanding contemporary artists, such as the IRWIN collective, Igor Eškinja, Luiza Margan, Goran Petercol, Mladen Stilinović and Vlado Martek, at his Golo Brdo studio between 2007 and 2020. Since mid-90s, he was invited to numerous exhibitions of contemporary art across Europe, took part in residencies for artists and joining several art collectives (Delta, an art-design community housed in the abandoned Rijeka shipyard).

In terms of artistic expression, Brajnović is closer to conceptual art, which put forward the idea (rather than the form) as the purest expression of artistic creation in the 60s and 70s and was especially influential in Croatian cultural environment. The “giants of contemporary art” such as Mladen Stilinović, Vlado Martek, Ulay etc. influenced Brajnović first as part of the academy's curriculum, then as artistic colleagues and, some of them, friends.

He does not see himself as a prophet; his interest lies mainly in philosophy and he places artists on the same level as philosophers. His works hold a mirror to society and often offer alternatives and different ways of thinking. Brajnović tends to strip human interpretations/imposed societal meanings from dominant concepts, ideologies, and phenomena, emphasizes hidden contradictions within them and shows them in a different light. He is especially focussed on Christianity, the most influential institution and spiritual heritage of our time, as well as social systems such as education or politics.

In doing so, he uses numerous ways, sometimes only small subversions, tiny changes of meaning or materials, minute interventions. By simply adding a single letter to his In Gold We Trust (No. 2), this Anglo-Saxon saying shows itself in a completely different light. Other times, for example in his Mozart (No. 7), a technically more elaborate art piece, he employs a professional crew to record a video based on a discovered school notebook to create a "visualisation" of the intrusion of ideology into the school system.

Brajnović is more rational and less dramatic than his father, using text as a crucial element of his work and emphasising the concept rather than a symbolic object. Following in the footsteps of the conceptualists, he does not limit himself by the medium (painting, sculpture). The medium is subordinate to content and Brajnović constantly employs the one that best highlights a certain idea. In accordance with his underlying ideological rationale, he also only exceptionally creates new – in his view unnecessary – objects, and even then, these are mostly video or photo documentation of projects.

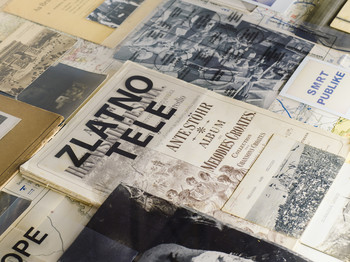

He owns an extraordinary collection of old pots and pans, glasses, fabrics, works of art, books, a kind of a creative archive, often using it as inspiration and constantly adding to it. He uses these objects as elements of his art, sometimes simply adding text to a readymade-object in the style of Duchamp's urinal, but mostly intervenes in them and/or combines them into new totalities. For Brajnović, it is the spiritual value of objects, rather than their artistic or historical importance, that is essential, which is why he interferes in them so boldly. For example, he screen-printed a text on an original 19th century etching and combined it with an audio piece to create Artist is a Soldier in a Ripe Wheat (no. 15). Objects are for him merely vehicles for conveying the artist's ideas, and contain no intrinsic value in themselves.

For Brajnović artifacts are not a goal, but a way of expressing certain content, strategy and form. This is why he, since the 90s, has been devising parts of his projects in public space, with the audience as an integral part. The rise of social networks, especially Facebook, provided the ideal medium for that particular part of his practice, where he often effectively combines the visual (photography or video, usually documenting an event) and textual parts. This particular means of interaction above all allows him to address a much larger audience and enables a more direct, rapid, spontaneous communication through comments.

He has continued to exhibit in museums and galleries, because he sees exhibitions as a complementary and equal platform to interacting via Facebook, podcasts and media appearances, all of them as different communication channels for conveying his ideas to different audiences.

Brajnović’s ways and means of art production put him in a similar vein to contemporary social scientists, who try to re-historicize, change the established interpretations, social paradigms, morals, ways of behaviour and thinking. But he takes it a step further. He is convinced that it is no longer possible to rethink the world anew within the existing models; it rather requires a radical shift of consciousness. He is aware that his worldview can get him labelled as conservative and narrow-minded by artistic circles, mainly because belief in God or the idea of God in the field of science and, perhaps even more so, in contemporary art is understood as reactionary. His position entails a broader vision, one that does not exclude the possibility of the existence of God, and so, in a way, a reunification of the two worlds (religious and non-religious, inseparably divided after the French Revolution), as well as posits the thesis that the world must be seen as a whole and cannot be conceived within narrow ideological frameworks.

This rings especially true in our time when technological development is overtaking reflection on technology’s meaningful use for humanity and shows that we are accelerating towards the wrong goal, a technological and not a human world. Since 2016, Brajnović has thus used several works to predict a total reset of humanity, an Armageddon.