I Made This So You Can Walk Over Me and Know It, 2021

The walking surface made of coloured concrete (2 × 4 m) features a silhouette of the artist, which the viewers can walk on. The title explains the work, while also serving as the artist’s means of directly addressing the viewers.

Family Table, 2021

An antique dining table found in the attic of an old farmhouse relates to the concept of the nuclear family. There are sharpening stones embedded in its surface, allowing the entire family to sharpen knives together instead of the family ritual of having lunch or dinner.

Wear V–VI–VII, 2005–2008

The triptych explores the cyclical nature of day-to-day life, i.e. the basic structures of an individual’s day. The steel objects illustrate a sequence of three phases: getting up (Wear V), arriving at the workplace to perform a repetitive task, each movement “rewarded” by a blow to the head (Wear VI), and an afternoon that is all about switching between TV channels (Wear VII). The last structure includes two television screens that have no signal and must be moved by the viewer manually. The white noise (snow) displayed on the TV screen symbolises the meaningless content that the viewers consume passively. The larger screen plays a video performance by the artist, using montage and background sound (from the films Beverly Hills Cop, Star Wars and The Patriot) to highlight the strain of the day-to-day routine.

Wear XXI, 2015

Moving a scrub sponge triggers a mechanical system built from pulleys, cords and a wheel, which activates an analogue “screen” set into a small old table. On this screen, the artist is “shown” while sleeping. The viewers doing the work thus keep the artist asleep.

Wear XXII, 2015

This work is part of a series of small analogue screens that operate only when viewers are physically involved. A simple turn of the crank is the only thing needed to make the artist start walking.

An interpassive relationship is established; as part of it, the viewer activates the piece of art through his/her input, while the artist remains passive, yet at the same time visually “active”. Thus, a reversal in the established artist-viewer relationship takes place.

Wear XX, 2015

The analogue “screen”, set in a decorative picture frame, is activated by the viewer rotating a hammer, which drives a simple mechanism via a shoelace. The collage shows the artist, dressed as a ballerina, dancing. The viewer makes the art piece work through his/her physical effort.

This is Furlan’s humorous way of commenting on the position of the artist – the viewer activates the artwork and in turn the artist “performs” for him/her.

Tunel, 2025

This spatial piece consists of silhouettes of the bodies of randomly selected individuals, which form a passageway. Concrete strips shaped like different bodily contours create a non-uniform and only partially functional tunnel. This lack of uniform shapes makes moving through the crowd difficult both in a literal and metaphorical sense. The work explores the possibilities of objectifying bodily diversity and creates a space through which the visitors enter the multitude of people, both in a physical and symbolic way. The installation explores the relationship between the individual and the collective and represents this relationship through the bodily forms that make up the space.

Border Not Working, 2019

The walkway-shaped installation consists of terrazzo slabs containing crushed stones, which have been transported across a national border. This work explores borders as a social construct, raising the question of migration as an ever-present part of human history. The walkway winds through the gallery space, i.e. it demarcates it. To be able to continue viewing the exhibition, the viewer must cross the border.

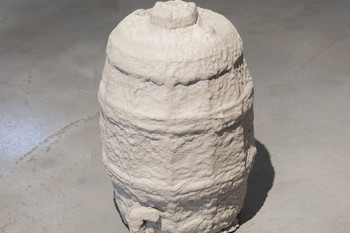

Useless Object I-III (2025)

Wheel, Ladder, Barrel

The artist used a concrete sprayer to transform three everyday objects – a wheel, a ladder and a barrel – into their totally useless versions. Some of them had been partially functional to start with, now, however, none of their usefulness is left. The artist’s intervention and placement in the gallery space has turned them into artefacts that encourage reflection on art. The series raises questions about the function, history and perception of objects. The starting point for the reflection is a note from the artist’s sketchbook, in which he reflects on the need to cover historical objects with something, thus rendering them useless.

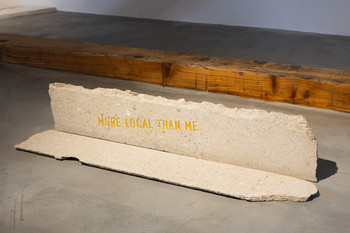

More Local Than Me, 2021

In the courtyard of an old stonecutter’s workshop, the artist randomly collected some slabs of stone – remnants of an activity that bear witness to the architectural and cultural heritage of the local community. The statement the artist has carved into the collected slabs emphasises that in a geological, cultural or historical sense, each of these slabs is more “local” than the artist himself will ever be.

All the Things My Grandfather Did I Am Not Allowed To, 2025

In terms of content and form, this work belongs to the More Local Than Me objects. It is a concrete architectural structure with two passages. Its simple geometric and minimalist design is reminiscent of the modernist era, which adds a dimension of the (semi-recent) past. The inscription on the “monument” has not been carved in full; the tool next to it allows for the possibility of the viewers’ intervention. With the statement that makes up the title, partly written on the object itself, the artist draws attention to the relatively short time span between individual generations (for instance, between a grandfather and a grandson), while also emphasising the extensive, diverse and subjective nature of retrospective memory. Through this artwork, the artist reflects on the way the understanding of the present is shaped by the dictates of selective memory, which influences the assessment of reality – for example, through the question of whether back in the day things were better or worse than today. The work is a response to the distorted perception of the past, in which anyone can participate providing that they think they can.

Scrapes, 2021

The symmetrical grid is made up of modular concrete elements that can be stacked ad infinitum – or at least until the material runs out. The elements are cast from the scraps found in the front yard of the artist’s own workshop: worthless mineral bits, fragments and sandbox trash are mixed up to form a concrete mass and then cut into identical units.

This work of art stems from a concrete, pragmatic need – to tidy up and organise the workspace. The act, however, goes beyond an everyday chore. The artist reorganises the seemingly useless material, which results in a sleek structure that satisfies the need for order and aesthetics.

Manual for a Home-made Spacecraft III, 2019–2025

This installation is the materialisation of a lost science fiction story written by the artist years ago. Its basic premise, written out on the screen in a way that resembles the opening credits of science fiction films, takes viewers to the near future, where the Institution is the overlord. In a world that no longer provides enough work for everyone, each individual is given the chance to build their own spacecraft and take off into space. The only obligation imposed by the Institution are regular journey reports. On the second screen, a promotional video of this imaginary Institution is played – it is a collage of images and statements, including ones by iconic figures from the world of art.

The first version of the project focused on an object that simulated a spacecraft, composed of everyday objects painted in neutral grey. With the simplicity of its design, the artist aimed to raise questions about the attitude to state-of-the-art technology and multifunctional devices that are supposed to optimise people’s lives. The second version centred on the bureaucratic apparatus and the collective effort to make the space trip happen. And this latest version focuses on the individual motivations behind the so-called traveller’s decision to embark on the journey – lack of work, the need for a challenge and wanderlust. The narrative is placed within an imaginary garage where the spacecraft is being built. The traveller’s intentions, along with the bureaucratic procedures he faces, are conveyed through inscriptions running across the floor – an integral part of the installation.